Kobun’s Recommendations for Sitting Outside the Zendo

We don't know where Zen is. Sometimes Zen doesn't exist in the Zen temple or Zen monastry. In a strange place you find Zen still alive. It can be questioned whether we always need to be sitting indoors, facing a wall. Under the Bo Tree was a protected spot, lots of oxygen, shade, no direct wind or rain. These are things common to the way we build a house, instead of sealing yourself in a solid concrete building. Staring at a cliff, tree trunk, or water could be like facing a wall. A river bank, or other outdoor spot, could have objects which excite you, but soon they become a blank wall again. The Buddha needed a stable rock and munja, a grass which can be bundled to make a soft cushion. The point is what sitting is.

You do not necessarily carry zazen around. When we travel in unknown places from one spot to another, we have to stay still for some time, to find out where we are, to find zazen. If you have an address to find, there is already a goal, so it's not a completely unknown place, yet, in the confused, chaotic bundle of burning life, itself, there is no address, so to speak. There is no one spot, no person, no particular matter from which you always measure your location. As long as your sense organs are functioning, settling your body and mind in a certain place eventually gives you a standard spot from which things can be measured. Instead of a standard measuring point looking toward you, in sitting, you create that standard measuring point. Our human mind rarely does that. Our mind usually goes around and around an object and finally obtains it.

The early practicers sat alone, unlike the monastic situation and practice. I know that you sit alone at home, and even when you come here and sit in a circle of people, you are still sitting alone. Of course the other people exist, but in terms of your own sitting, you are always doing it alone. The kind of sitting we do, that we are each devoting time and effort to, is varied by the understanding of each person. There are many details of helpful instructions, but each sitting, itself, does not require all those details. But because we were born as a human body, our conditioned form, there are various instructions. "Who sits?" is the first question. When you sit, you set aside the idea of you, yourself, as sitting. Set those ideas aside. You don't stick your personal, individual idea or opinion into it and use sitting for your achievement of some kind. Eventually you find out that was the wrong way to begin.

Any place, any time, is fine, as long as it is not too exposed and dangerous, or just when the family is beginning a meal! You do not, because you feel an urge, excuse yourself and go to your bedroom and sit, or maybe you sit down next to the table! That's too inconsiderate. The best time is when people are not aware that you are sitting. Continuous impulses coming to your body should be avoided, like sitting next to the refrigerator. In the bedroom, beside the bed, maybe that is the very best place. We have an instinct about where to place our sleeping spot and a similar sensitivity should go with the sitting spot. For a very beginning person, to begin to understand the reason for sitting, it is a good idea to make a certain time to sit. But when people have sat for some time, sitting should freely appear. The length should also be very flexible, too. Sitting for long periods, for many months or years is not encouraged, although we do it. Periodic contact with people, anybody, is necessary. Intentional sitting because we have a problem is a very poor choice of time. The best way is to choose the time when you are in the best physical condition. When only problems tell you it's time to sit, you will experience only very hard sitting. You notice this when you sit in sesshin. You know the best time of day for your body condition. Only you know. I cannot tell you the best time to sit.

Sitting by the beach with the constant sound of wind and waves is fine for a short time, but for many months and years, it's not quite recommended. Inside of the house by the ocean is fine. Our mind is a mysterious transformer in it's creativity, and it eventually transforms external impulses. The hardest one is the human eye. Do not expose your sitting to most human eyes. It's a very strange thing to say, but of course, sitting is not a show case, so it's not a question of how it looks. Rather, we want to be most obedient to our urgent need of sitting. There is not much chance to find the ideal place so you have to be satisfied with maybe a fifty-per-cent favorable spot.

Remembering your own experience, the first time you saw somebody sitting, you recall a strong, I don't know what to call it, fear, or shock. "What's going on with that person?" When I sit in sesshin, I recall a movie I saw, in which there was scenery of Nepal, and an aged yogin was sitting. Now, I think his posture was not quite good, but the atmosphere of it was very striking and impressive to me. His eyes were closed. In another scene, someone came to offer some gift in front of him. There were big mountains behind him and flower beds everywhere. He had a long beard, was almost naked, with dark brown, white hair, a little black hair here and there. When his eyes opened, they were unfocused, almost white. I thought, "Oh, no! When you sit you become like that!" The practice of tapas with eyes open in the hot sun made him like that.

The point is, you have to start from the very inside of you. Don't just carry this clumsy body onto the cushion. You are not searching or seeking something outside, but something is burning inside you which carries you around. It's like the burning fire which Zarathustra has to bring to the world. Usually we say, "way-seeking mind." You have no choice. You have to take care of it. It is not self-made. Like a seed, when it gets the right conditions, the right elements are magnetic to it and it starts to grow. You cannot think too much about sitting and what it is. Just do it.

Bodhidharma sat in front of a cave wall, but we don't know what he saw. We are not in a movie theatre waiting for the projected movie. You are the projector! Whatever comes, about the future, about the forgotten past, important things, you stay in the present moment. For one second, one split moment, the wall is not there. If you were practicing archery, you would set the target and find a safe spot from which to send the arrow. What you would observe is the physical dynamics, the balance, not the target. So I would say that the wall you face is not quite a wall, rather, it is a meeting with you. It's easy to see nothing is there, instead of having a constant image of a teacher or friend. It's blank. It saves you, reflects you.

There are many contemplative practices: Moonlight sitting, sunlight sitting, snow sitting, rain sitting. Whatever nature's condition is, you sit in it and find out both what it is and what is yourself. You find out how it is to live in those conditions. Counting breath is also one technique, especially recommended for a busy-minded state, when your mind cannot stop jumping from one thing to another. It's probably a chemical imbalance! In this state you can't relax in the present moment because this computer mind goes on and on, and your emotions change from one to another.

During sitting, you have memories of occasions, re-experience your past instants. You are able to become the audience, re-examining what it was, what was actually going on, until you are ready to observe it correctly. Then the emotions start to unfold again. This kind of pain, joy, is real, but actually it is not quite real. Conscious memories of your deeds, karma consciousness, and emotional reactions to them, are finished every moment. You observe it and accept it, letting it go. If you continue to stick onto some part of those exeriences, you continue charging up your emotion every moment. This doesn't do any good. All along you have a sense of what it is which senses this suffering. We have to understand that. The one who is breathing in and out, in and out, that doesn't suffer. But it does sense suffering.

We live in a world of such strange rules, so we have to look at what's going on. Daily life is full of dilemmas, but in order to understand, and possibly admit that is our human condition, unnecessary worries disappear and necessary worries we have to find. It is a very good subject to work on.

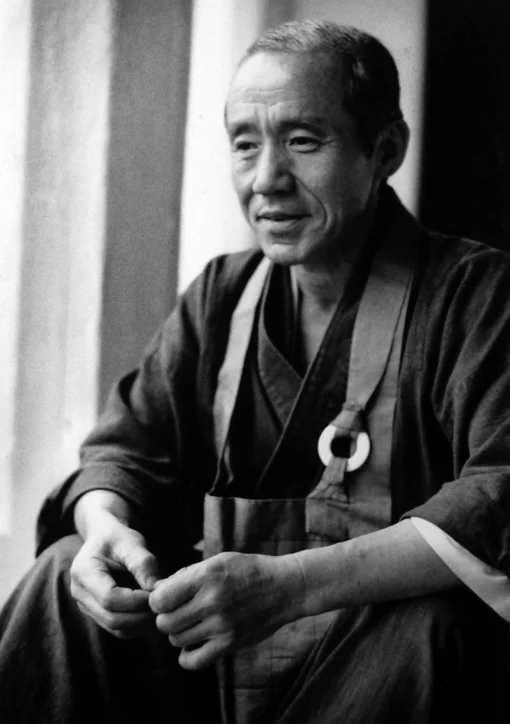

Kobun Chino Otogawa