Despite growing up in a microcosm of teenage zen philosophers, not a single one of those ideas managed to bring me though the door of a zen temple. Instead, I fell into zen while simply trying to shut the incessant narrative in my head off. I started with a copy of Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind and after that, when the alarm went off, I had coffee and then the dog and I sat on the floor in whatever town I lived in before we went to work. I built houses and worked with horses and sometimes I would see the word Dogen in a book I read. Zazen, seated meditation, was good for what I did and I started meditating in the truck and in the barn. Sometimes it got my ego out of the job of micromanagement and created a stillness from which my body could whirl from thing to thing to thing. Zen was not an idea, but a feeling, something I thought of as being on the beam. Sometimes I was there. More often were the times when I was sure I was on the beam until I encountered one of the many moving objects in my world. The creatures inhabiting my world seemed to come alive in a new way and I began to realize that language was way overrated. Zazen was about listening with my heart. So I got excited about meditation and started asking my friends a lot of questions about zazen but got complicated answers. Eventually, one of them mentioned that they didn't actually meditate. I found this puzzling and kept sitting. Finally, they invented the internet and eventually I figured out how to find a teacher, which was a good thing because my legs kept falling asleep. There was a lot to read and a lot of of people to talk to and many of these words have helped me in my journey and sooner or later most of the signs at the zen centers always seemed to point back to the monastery. So I did some math but the results dismayed me. It would take at least 100 people giving 1% of their livelihood to support me in mine. This meant that at least 100 people had to keep suffering for me to follow the Japanese Monastic road to enlightenment. Clearly, American zen was going to have to be something else. For me, the road led not toward finding a place where enlightenment was possible but to finding a way to engage with the

world as it is. It was on that road that I encountered Victoria Austin.

These days, Victoria Austin lives at City Center, The three story temple in San Francisco that Suzuki Roshi created with his life. While I was sitting in the dorms with my friends talking about whether or not we actually existed, Victoria was ordaining as a priest. She noticed early on that zen was not something you thought but something that happened inside your body and I have yet to hear her talk about zen without mentioning the need to find ways for people to wake up where they are.

Victoria began her training as an architect and then began her zen practice with a ground up approach, quickly discovering that the foundation of practice was located in the body. She read the sutras and it became increasingly apparent to her that it was no accident that Siddartha Gotama was a yogi before he was a Buddha. Also, as she continued to read, it dawned on her that the sutras she was reading were originally spoken to circles of people immersed in a culture where yoga was common practice. It became obvious then that she was going to have to go to India and study the body there. The Iyengar family knew a lot about yoga so she found them and has taught yoga as a practice for twenty five years.

"Zen," she will tell you, "is a form of yoga."

Some people you meet by accident, others you meet intentionally. Victoria Austin was way too busy for me to meet accidentally.

The need to meet her arose when Darlene Cohen left this world before I had learned enough about posture. A few months after her death, feeling a little left behind, I went to my teacher, Kosho, and asked,

"Who studies physical practice, I mean who teaches posture and how to work with the body in zazen?"

"There's Victoria Austin," he said, "and after that...well there really isn't anyone else."

A few weeks later I was on Plane to San Francisco.

Victoria Austin does not talk at all like a guru in two mystical foreign spiritual practices. Being an architect, she spoke to me right away in a language I can understand.

"The body, she says, has two kinds of structural strength; Column Strength and Tensile Strength. Column strength we get from the bones, from aligning the spine so that it carries the weight of the body. Tensile strength comes into play just like the cables of the Golden Gate bridge. We want to balance the tension of the muscles so that we can sit naturally upright with ease...."

From there she started to talk about the breath and after that I went to work...

The thing your average buddhist spends the most time on is watching the breath. Dauntingly, this simple practice immediately becomes frustrating as the ever helpful ego steps in and tries to run the show. The next thing you know, you are sitting there with a growing feeling of awkwardness which occasionally transforms into another feeling...growing suffocation. From there, myriad forms of hilarity can ensue. The ego, it turns out, is really not good at respiration. Thus, we practice with the breath for exactly that reason.

There are very few places in the body where the voluntary and involuntary systems of the body coexist. We meditators could work with swallowing, but that would probably end badly in some form of choking. Instead, we try to teach the mind to align itself with the body by asking it to sit down quietly next to the subconscious mind just as we would do if we were trying to get as close as possible to a wild animal. If we were trying to touch a wild animal we would sit every day near water at dawn and dusk, waiting quietly for the animals to gather. In zen, we go to the breath, quieting our thoughts, trying not to move as our emotions and impulses arrive at in their rawest natural forms.

In doing this, we start to notice that it would be helpful for our lungs to move easily, unfettered. And fortunately for us, Victoria Austin, the architect, has a gone to the trouble of turning the teachings of the ancients into a practical blueprint of sorts. In it, our inherent structural strengths can be used to open the lungs.

Here's how to build a structural framework for the breath:

As practices go, this one is a little more complex. Of course we zen people always want to do one thing at a time but this particular practice involves herding a whole group of things together that are scattered on the range. Later, you can move the whole herd. But cattle drives always begins with a round-up. Your ability to expand your rib cage will depend on the underlying work you've done with the spine and will require a basic inner agreement that the ego will limit it's interference with the operation of the lungs. You should have spent a lot of time by now on Suzuki's basic instructions, pushed the crown of your head up, dropped your chin, and have a healthy relationship with your spine. The focus of what I am about to tell you is about tensile strength so you will need to have your column strength, your basic spinal posture, already well established.

Been there, done that? Then lets get to work.

First off, our inner awareness is going to require a knowledge of anatomy. We will need to know what we are working with. Because we will need to put specific muscle groups to work, we will have to find them. Also, we are going to use our muscles in two distinct ways. Some of them we will contract, to shorten the bands of fiber as a means of bringing two bones closer together. Additionally,we will need to learn to energize and inflate other muscles for use as a means of support.Begin by looking at your hand. Open and close it a few times. Now, spend a few minutes feeling the sensations of the muscles that operate your fingers and find the points at which each muscle is anchored at either end. We're not doing zazen yet but this will teach you to develop the awareness required to find and contract a specific muscle.For the second technique, focus on your hand again and find something in front of you to lift and get ready to pick it up. Don't move yet. Just get the hand prepared for action. Now, feel what you've done. Feel the energy that has moved to the hand. This feeling of

readiness

is the second thing we need to learn to bring to our muscles and Shunryu Suzuki talked about it all the time.Practice with this a little more and then let's move to the cushion.

OK, lets start with the rhomboids. We want to move the scapulas so that they are in a line with each other and the shoulders are pointed straight outwards. If you are American and reading this blog, you have probably spent a good part of your life leaning into papers and books. This of course moves your head and shoulders forward and there is a 90% chance that more air would enter your lungs if you would move your shoulders back. If at all possible, find someone who can tell you if your shoulders point straight out or are curved a bit forward and if your shoulder blades are in a straight line together. This is where a Zen teacher really comes in handy and is a free service offered at your local temple.

Odds are that it's time to move your shoulders back to a natural position and into a human posture which predates the cathode ray tube. Looking in the mirror, we notice a conundrum, as we move the shoulders back to open the chest they also rise, tightening the chest and end up being suspended by our muscles instead of hanging naturally on the spine as originally designed. This of course creates tightness and tightness leads to emotional irritation and emotional irritation is not why we sat down on this cushion. This is related to the second problem with being American; inventing a self and trying to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps all the time. Almost invariably, the American self discovers that raising the shoulders makes us appear just a tiny bit larger than life, leaving us, by adulthood, convinced that the muscles above the shoulders are what move the shoulders back. They don"t.

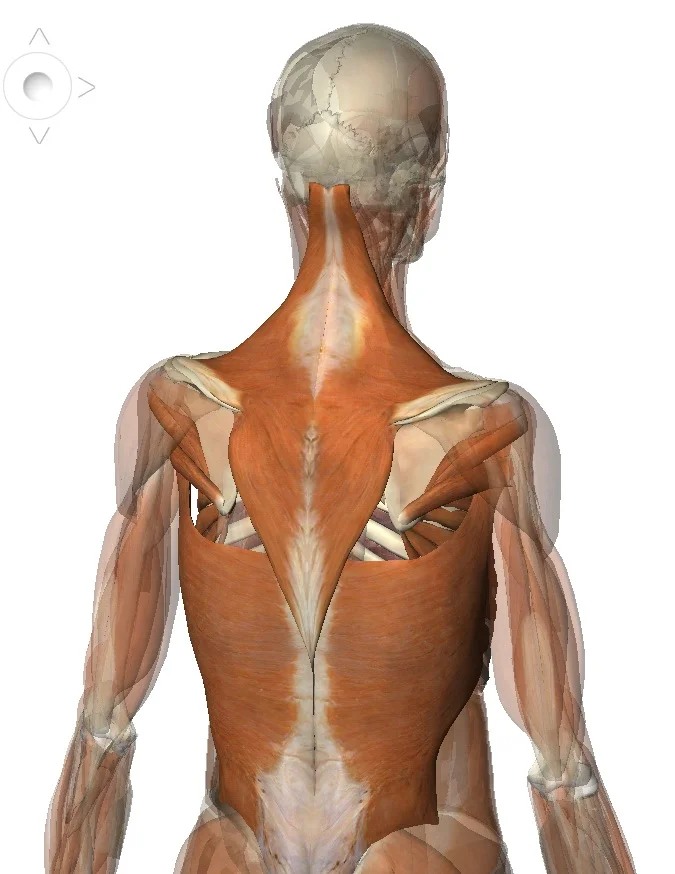

The dark bands of muscle in figure one, connecting the shoulder blades to the spine, are the rhomboids, designed to pull the shoulder blades back. Try them out now, and watch what happens to the chest. As the shoulder blades move back and align along a single plane, the chest moves forward and up, the rib cage enlarges, creating more room for greater expansion in the lungs. There may be a tightness in the chest at first, as the pectoral muscles are spread across a wider expanse, but this will fade as you settle into your new posture. Go ahead and start the long process of relaxing the muscles of the neck now, allowing the shoulders to drop into their natural position, letting the collar bones rest atop the thoracic cage, transferring the weight of the shoulders to the spine. The rhomboids are now involved in your zazen, doing the heavy lifting to open your lungs. Within a few minutes, a slight burning sensation will inform you that the rhomboids aren't yet adapted to your practice, so begin the process of developing them, holding them in position as long as you can, relaxing, and then pulling them back into the form. Over time, this will integrate itself into your posture as comfortably as the muscles that suspend your head as it leans forward into the screen.

Which leads us straight to step two. We will need to pull the head straight back so it sits directly atop the spinal column, it's weight traveling through the vertebrate straight into the hips where it can be directly transferred to the cushion. This importance of this becomes obvious when we remember that the head weighs roughly the same as a bowling ball. A bowling ball becomes an increasing burden to bear the further outwards we hold it. As the head moves back, notice how quickly and insidiously the neck muscles involve themselves, raising the shoulders and shrinking the ribcage. The result is less space for air. So we're back to isolation, tautening the specific muscles positioned to create the motion we want, while relaxing the muscles that misdirect the movement we attempting. Another search through the handy anatomy app tells us that the trapezoids are just the thing we need to bring the head in line with the body. Looking the the trapezoids, however, we discover that the trapezoids are attached to shoulder. Since lifting the shoulders will transfer their weight from bone to muscle, in order to take advantage of the column strength of the spine, our work is going to have to get nuanced.

Dogen said, "to study the way is to study the self," so, for the moment, lets study the trapezoids. While most muscles are a reasonably simple bundle of fibers designed to pull one thing in one direction, the trapezoids appear almost like an amorphous alien hitchhiker, attaching itself to the shoulders, spine, head and upper back, and functioning based on subtle contractions. Unlike the biceps which seem follow a flex/ release range of motion, the trapezoids can contract in an undulating fashion to move the upper body through a wide range of movement. So in order to move the head into an upright position that we can relax into, we are going to have to get sinuous.

We want to be able to flex part of the trapezoids while relaxing the rest. Our intention should ripple through the muscle fibers, awakening them at the base of the head, then cinching the head back as the movement travels downward along the spine. The chin should drop slightly, as the head finally comes to rest centered atop the spine and the the trapezoids relax with just a whisper of effort remaining to keep the head balanced.

Allow this weight to awaken the body and the let the energy that meets it to follow the supple curves of the spine upwards, like a cobra rising from the earth.

To support this delicate balance, we can draw on the strength of the body's core and use some of the large muscles to provide additional stability and to build a set of outer walls around our column. What we want to do next is bring Suzuki's 'readiness' to the latisimus dorsi, the large muscles which, together with the abdominal muscles, make up the band encasing the lower back. Running from the armpit to the tailbone, the sheer bulk of these muscles, when activated with just a little energy, become a formwork to encase and support the shape of our core and a platform on which to rest the weight of the shoulders. Our posture is largely in place at this point, so rather then flexing the lats, we instead merely want to bring enough energy to them to involve them in our stillness.

Think of the exercise with the hand now, and bring that feeling to the lats and awaken them, involving them fully in our zazen.

Keeping this invigoration in mind, move to the serratus muscles, which are the suspension cables of the ribs, tying the weight of these bones back to the spine. These take a little work to find, as much of their action is involuntary and they rarely attract the attention of the self. Too much tension and the thoracic cage starts to compress, too little and it begins to sag. Refresh these support cables then without applying tension, allowing them to fill with the electrical impulses and blood that will inspire their work, expanding the ribs and pulling the sternum upwards and out.

Check the small of your back now and listen to any pain that may be trying to tell you about any excessive curve in the small of your back.

And finally, after all this winding up and inflating of tissue, we come the final adjustment, returning to the shoulders where we started, look for teres major and minor, the rotator cuffs, the blue muscles shown in the figure to the right. Holding the shoulder blades in place with the rhomboids, tighten the rotators just enough to balance the shoulders, and ease them back into alignment with the spine. The points of the shoulders should face straight out.

Now, as Darlene Cohen never stopped saying, look at what you've done. Perhaps you might be wondering how in blazes this could possibly relate to Dogen's promise of repose and bliss, but stay with with me just a little farther up the road. Let's leave our first reactions behind for a bit and see what we can find. Thus, without moving the shoulders, bring your hands to your hara, inhale deeply, completely inflating your

lungs, then relax the abdomen and settle into a natural breathing pattern, or at least as natural as you can given your rigid new posture. Pay very close attention to the movement of the lungs.

Quickly, you should discover that despite the rigidity that comes with radical posture tuning, the lungs are able to take move air more easily, into the expanded volume of the their housing. The lungs, at least, are able to move effortlessly. It might dawn on you, that perhaps if your rhomboids, trapezoids, latisimus and serratus muscles, teres minor were a little stronger, and a little more toned, this posture might become easier.

So now it now comes down to an ideological question. How much effort do we want to put into our zazen. If your answer is a lot, then examine these illustrations and get thee to a zendo. This work follows the same regimen as lifting the hands; hold the posture until it hurts, hold it a little longer, and then relax, rest, then realign yourself again, and put some tension back into your muscles. This is exercise, so maybe its not so good to fill the entire period with this work. Over time, and I am talking months, the muscles in your core will grow, and tone, increasing their ability to relax while maintaing their position and form. Gradually, the spine realigns and your posture becomes sustaining. The thoracic cage will expand and you will have redefined natural. This framework for your breath is created by the simple holding to what is an ideal now, relaxing and returning over and over again until you grow into to it.

And yes, it is busy work to begin, but over time, the many things will become one and you will gain a sense of what Reb Anderson means when he talks of being upright.

Alternatively, If the timeframe seems a little long, if you wanted to develop these muscles at little faster, you could always do what I did: first, go to a practice period with Victoria Austin. While you're there, start running. Make sure you run a lot further than you have ever run before. Six miles a days works if, like me, you are a new to running. Ignore all pain in your knees. Keep running until the MCL ligament in your knee fails. Two weeks should do it. After the doctor pulls you out of the zendo, feel sorry for yourself for a few days while your leg is elevated and then when you can't stand it anymore, try going for walks on your crutches until you realize that you are too tired to make it to where you were going to go. As the knee heals, and the cabin fever sets in, start going faster on your crutches until you are doing this weird distortion of jogging. When they send you back to the cushion, your new posture, while not completely natural yet, will be not only painless, but the air moving fluidly through you will carry you to a new depth in your practice. Oh, and write a blog.

Because the thing I didn't realize until I created the illustrations for this little article was that the whole time I thought I was out of the zendo, it turned out that the crutches were a power workout for my posture. The motion of crutches is to move the entire weight of the body by pushing the chest upward and outward. That's the thing I keep forgetting and rediscovering about Zen. We are not always in zazen, but the simple act of being alive means that we are constantly cross-training.

See you on the mat.